In 28 Days Later (2002), we followed Jim (Cillian Murphy) as he awoke into a desolate London overtaken by the rage virus—a hyper-aggressive infection that turned people into sprinting, red-eyed monsters. Since then, the franchise has chronicled the fall of civilization (28 Weeks Later) and now, with the third installment, 28 Years Later, we shift focus entirely.

No longer are we in the heart of urban England. Instead, we begin on a remote island sanctuary, Lindisfarne, a tidal island off the coast of Northumberland, also known as Holy Island. Here, we meet 12-year-old Spike (Alfie Williams) and his father, Jamie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), just as Spike is preparing for his first mission to the mainland—a rite of passage that quickly unravels everything he believes.

This third installment hit theatres in June 2025. Should you be fortunate enough to have stumbled here and have not seen the movie yet, I encourage you to do so! If so, don’t read ahead to the next section, as I’ll be going into a spoiler-heavy review of the movie.

Reading Ahead

Before we’re introduced to any of the central characters, we see a room full of children — aged around 6-11 years old — watching Teletubbies. Each of the children are noticeably distressed, with some of them crying. At this point, we’re no strangers to this franchise, and can already anticipate that there is likely a hoard ripping through the surrounding area, and on their way to them. One curious boy, Jimmy, stands by the door until a rapid and consistent thudding persists on the other side. As is the standard, the infected are able to break through the door and we see them storm through the room of young children, blood splattering on walls and besmirching the Teletubbies screen. Jimmy manages to escape to a church, and a pastor hands over his cross chain before the boy hides and the pastor is killed by the horde.

After this point, we’re introduced to 12-year-old Spike (what the fuck, I literally just found out that Spike was short for “Nicholas”!?) and his father, Jamie, getting ready to go out on Spike’s first venture onto the mainland to kill an infected. We learn two important things early on: One being that Spike’s mother, Isla (Jodie Comer) is very ill to the point her mood and cognitive abilities are significantly in flux. She is mostly bed-ridden in the beginning of the movie, complaining about headaches and being generally confused and uncomfortable.

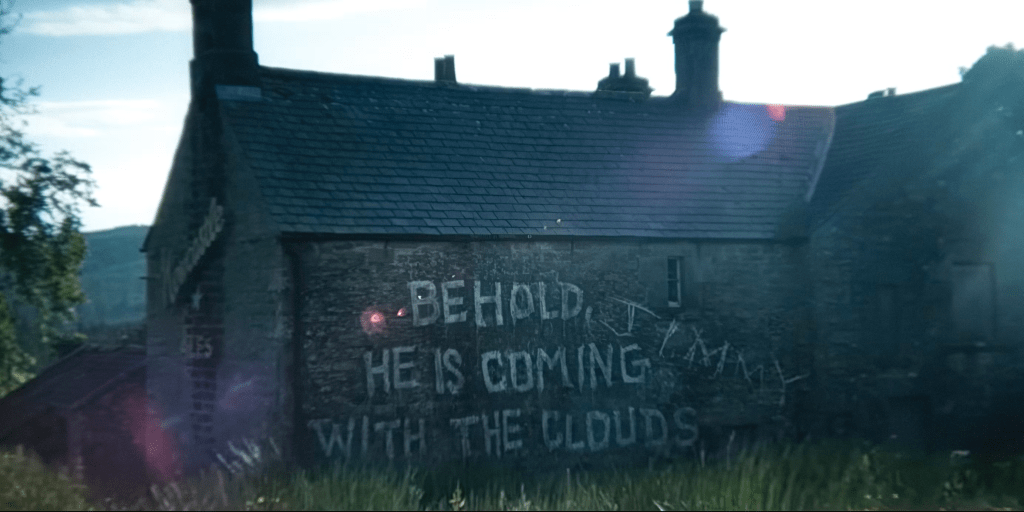

One of the council-people had snarkily noted that this ‘tradition’ is mostly standard after someone turns 14-15 years old, so it’s quite odd that Spike is doing so significantly earlier. Jamie harps on that Spike is ready to go, and they set off. On the mainland, Spike and Jamie encounter three types of infected: the fast-moving Runners we’ve seen before, the slower and grotesquely obese Crawlers, and terrifying new Alphas — more intelligent, stronger, and strategic. Unbeknownst to Spike, it’s also evident that nature has reclaimed a lot of the land, with vines and excess greenery present on many man-made structures, and an emphasis that man-made objects will fall throughout the film (the abandoned cottage, the bone tower… does this hint at an eventual — and final — collapse of sanctuary and vague civilization?). Spike kills a crawler, but the two are quickly veered off course by a horde led by an alpha. They take shelter in an abandoned cottage, before it collapses in the night and they make a run for it back home before the tide is completely low.

Back on the island, Jamie gushes about Spike’s bravery— despite Spike having missed most of his shots. The boy silently recognizes his father’s lies, and things worsen when he finds Jamie hooking up with another woman. Spike returns home to his grandfather, Sam, who tells him that there’s a “before-times” doctor still on the mainland, Dr. Kelson, who collects and burns corpses in a massive pit. This is the last straw for Spike, as Jamie assured him that formal doctors are virtually extinct, meaning Isla would eventually succumb to her illness and die without proper medical care or medicine.

With this idealized image of his father shattered, Spike confronts Jamie, and later sneaks out of the commune, taking his mother with him to find Dr. Kelson. In the time that they endeavor to find the doctor, Isla grows increasingly disoriented. She consistently confuses Spike as her father, which makes sense to the audience, given that Isla earlier confided in Spike that when she looks into his eyes, she sees her father — with whom she had a close connection with. They’re saved from a horde by a Swiss soldier named Erik. Soon after, Isla discovers a pregnant, infected woman inside a derelict bus. She helps deliver the baby—just before Erik shoots the mother. An Alpha finds the body, becomes enraged, kills Erik, and chases the other two, with Isla towing the newborn in hand.

Dr. Kelson intervenes, tranquilizes the Alpha, and brings Spike and Isla to his base, a shrine he calls The Bone Temple, made from human remains. He examines Isla, diagnosing her with metastatic breast cancer. In an act of mercy, he sedates her and burns her body, giving Spike her skull to place at the temple’s peak.

Spike returns to the island with the newborn, but leaves the baby at the gates, then departs again, writing in a letter that he plans to “walk until he can no longer see the sea.” On the mainland, he finds a group of flamboyant survivors (dubbed “The Jimmy Gang”) performing parkour and theatrically slaughtering infected.

The film ends with the leader — who we can assume is a now-grown Jimmy from earlier in the film, still wearing the same cross from the church — inviting Spike to join him.

What is the Extent of the Infected’s “Evolution”?

Nearly three decades post-outbreak, and the infected have diversified. In this movie, we learn about the following types in infected:

Regular ‘ole infected – Fast, feral, and mostly unintelligent/senselessly violent. They’re also noticeably complicit to Alpha demands.

Crawlers – Obese, very slow, quiet, and mostly unable to walk, thus they get around by crawling on the floor.

Alphas – Stronger, more intelligent, able to strategize and exhibit emotion.

I don’t think it’s cheap or strange that other types of infected exist in this universe now; however, I’m very interested in the Crawler type. It would make sense for me to assume that that’s what happens to infected overtime, considering joint and bone degeneration. But no, this is a specific kind of infected. This begs: How has the “rage virus” transformed into something that really is seemingly docile?

We see “alpha” zombies pop up in other apocalypse universes, so I don’t think the introduction of that kind here is odd. In fact, it does make sense that infected would adapt to their surroundings and become smarter (but maybe not inherently stronger in such a short time span, in my opinion) to fool and capture prey. However, there are many questions that come up from this: Are alphas ‘born’ or do they originate from ‘turned’ humans? And my most burning question: Can infected mate and produce offspring?

While the infected woman is giving birth, Erik calls for Spike to kill the baby, noting something like “they shouldn’t be allowed to mate.” I’m not super convinced this is totally what he said (I fear I rely on subtitles for the life of me), which still makes a bit skeptical. When the alpha finds that the pregnant infected woman has been killed and the baby is gone, he becomes visually angry and begins chasing the others. Was this his offspring? Did he mate with this woman before or after infection? Considering his obvious anger here, do alphas also have the ability to mate with other infected, and experience loss and other emotions outside of plain rage? Is this a relatively ‘new’ development among infected? If so, why weren’t the survivors (specifically, Erik, considering he has been on the mainland before) more shocked by this — or at least more vocal about their confusion?

When Spike first arrives on the mainland, he and his father come across several Crawlers, one of which is a child. This confused me a bit: It’s not strange for a child to become an infected, of course (we’ve seen that happen both at the beginning of this movie, and in the earlier two installments). However, this child is an adapted kind of infected; I wouldn’t claim it has evolved, since this kind of infected mainly crawls at a slow pace and seems debilitated by its shape/inability to walk for long periods of time. This questions: Was this a human-child-turned-infected that just became a Crawler? If so, does being a crawler (or alpha or regular infected) depend on prior physical and mental disposition of a host before infection? Or, did two Crawlers mate and produce this new, infected child? What would this say about Dr. Kelson’s theory of the placenta offering a safe haven to the fetus, if inside an infected woman?

Perhaps the most believable explanation is simply that the virus itself has splintered into variants: Alpha, Standard, and Crawler strains, based on transmission method or host compatibility.

Jamie’s Influence on Spike

Jamie embodies the rugged survivor, but beneath his stoic façade is a man fractured by trauma. He pushes Spike to kill, lies about his son’s success, and betrays Isla. His arc mirrors the toxicity of unchecked masculinity in crisis where performance becomes identity.

Conversely, Spike’s arc is deeply emotional. His empathy sets him apart from other characters hardened by survival. He was raised with stories of the apocalypse, not memories of it. He’s the product of a post-apocalyptic generation trying to reclaim innocence.

His heartbreak upon learning the truth about Jamie, and the loss of his mother, pushes him toward self-reliance. But by adopting the baby and walking away from both island and father, Spike shows us that his heart remains intact.

Later in the film, we do see Spike adopt a similar indifference to the infected that Jamie has, but the nature is different: Jamie has killed countless infected and has presumably had just as many close encounters with them. He has openly expressed that the infected are nothing more than husks of their former selves and should not be pitied. That’s not to say Spike doesn’t or will not eventually feel similarly, but I also wonder how the newborn’s presence affects his thinking around infected. Whatever it is, Spike doesn’t kill it. Thematically, that’s enormous. He’s not just sparing a baby — he’s refusing to kill what might come next. For better or worse.

Interesting Stylistic Choices (but only in the beginning of the movie?)

If you’ve seen this movie, there’s a part in the beginning, when Spike and Jamie reach the mainland, that almost seemed like an extended clip of the trailer for the movie, where actual scenes from the narrative are shown, then spliced with creepy, red-tinted night vision clips of infected looking at the camera or eating a deer carcass. All the while, that creepy audio from the trailer is playing (which you can watch above), which sounds like someone reading correspondence points on a radio and repeating “run, run, run.” Obviously, the elements that they chose to feature here are not strange and can be pieced together — yep, the infected are like vultures, we can get that while also being momentarily offput from the visual and audio. However, there’s no other sequence like this in any of the movies at all, nor does this happen later in the third film. I’m afraid it’s difficult to contextualize into words here outside of “it literally felt like a 3-4-minute-long extended clip of the trailer.” I won’t hold the producers or creators to this too much — it was certainly effective in making me feel uneasy during that point of the movie, but its randomness was also not lost on me.

That said, I assumed, “okay, so there will be some stylistic differences in how this is shot and visualized then.” You can’t blame them, as it has been 18 years since the last move came out. Outside of occasionally featuring the red-light clips of the infected moseying around, or a deer looking into the camera, this scene style wasn’t replicated at all later in the movie. I wouldn’t slouch at the entire movie for this, but I certainly felt like it was a bit awkward. Folks have been waiting almost two decades for this! It’s crucial to be as intentional and meaningful in storytelling as possible! But more on that later.

How Does The third Installment Meaningfully Contribute to the Franchise?

Each of the central characters do well to chart forward an appropriate and interesting addition to the 28 Years Later universe. For the sake of brevity, I’ll only discuss our three main characters.

Isla seems most representative of both life before the apocalypse and the immediate crash afterward — particularly given her dependence on medication and her cancer diagnosis (a “prehistoric” way to die, in contrast to the new norm of being brutally killed by the infected). Because of her condition, Isla often conflates Spike with her father, further emphasizing her longing for that safer, pre-apocalyptic world.

Spike, on the other hand, obviously represents a shift from innocence to “corruption” — learning of his father’s cruelty and becoming increasingly comfortable with killing infected. But on a larger scale, he belongs to a generation that has completely adapted to a life of semi-constant control and surveillance. His home on Lindisfarne underscores this: the island has no electricity and lacks most recognizable elements of pre-apocalypse life. Spike has grown up in a community that has regressed in many ways — one that accepts the infected as a part of the natural order. Aside from the general terror they inspire, Spike has only ever heard secondhand stories about the initial outbreak. That context may explain both his initial hesitation to kill the infected and his empathy toward the infected newborn. Someone who survived the early days of collapse might be far more jaded — having experienced the chaos and trauma firsthand, long before any sanctuaries were established.

My favorite character, however, would definitely be Dr. Kelson. Outside of using his “before-time” medical knowledge to concoct tranquilizers and cover himself in iodine (Pause: Why didn’t he just kill the Alpha immediately after he tranquilized it?), Dr. Kelson is the creator of the bone temple.

I did find it a bit funny that right after Isla and Spike encounter him, he immediately mercy-kills Isla. I get it — she’s been suffering for a long time, and tranquilizing her before killing her is presented as an act of mercy. But in the moment, I couldn’t help thinking Kelson seemed a little too eager to add to his collection. Like, damn, maybe give them a day or two, guy.

Jokes aside, Dr. Kelson presents one of the film’s most compelling ideas. In most post-apocalyptic narratives, a medically trained person would be considered invaluable — welcomed into any sanctuary in exchange for knowledge, safety, food, and community. And we know Kelson is particularly resourceful: he’s fast-thinking and inventive (coating himself in iodine because “the infection doesn’t like it,” finding ingredients to make tranquilizers, etc.). But instead of seeking shelter, Kelson rejects the reconstructed idea of society and devotes himself to honoring life through the creation of the bone temple. When Spike and Isla arrive, we learn the temple was built as a shrine to the dead — both infected and uninfected. Kelson acknowledges the shrine is temporary; it will likely be destroyed by weather or an Alpha. But he continues to tend to it anyway, maintaining and adding to it in an ongoing act of reverence.

This might be the film’s most significant contribution to the franchise’s broader world-building: a meditation on how fragile life is, marked by the most enduring organic material left from human bodies. In a world ravaged by violence and death, art becomes the clearest testimony to what it meant to be human — on the edge of extinction.

In honoring both infected and uninfected, we also have to consider Kelson’s relationship to the infected themselves. When he learns that an infected woman gave birth to a non-infected baby, he comments that he’d always wondered whether the virus could cross the placenta — and now knows it can’t. Does this mean he humanizes the infected? Is that why he doesn’t kill them, only stuns them?

What is a Jimmy?

Per the website, The Wrap, “Jimmy” refers to “Jimmy Savile, a British television personality who was, for a long time, an immensely popular and well-known celebrity.” Savile was recognized by his track suits, blonde hair and gold jewelry, all factors of which are present in our fabulous band of power rangers that appear at the very end of the movie. Should as presume that the man with the cross chain at the end of the film really is the boy from the beginning — which I think is safe to say — then his name is also Jimmy, as we know from the mother pleading for him and the other children to stay and be quiet.

I was a bit taken aback by the random parkour/hero-like ragtag group saving Spike at the end of the film (it definitely got some laughs around the theatre), but I actually really loved this element. The world ended, and a traumatized child who idolized icons from television childhood infused those them into his identity and way of life. With the earlier consideration of Spike being representative of the ‘new generation’ that has grown up with the apocalypse being the norm, Jimmy’s own upbringing being dependant on the apocalypse could also be interesting to consider.

Holy Island Entirely Separates Itself from the Mainland

In fact, it even seems that the Holy Island community has developed a kind of folklore around the infected. In an early scene, as community members prepare a long ceremonial table, one person dons a haunting mask — pale, with red paint streaming from the eye sockets and an arrow piercing through the forehead — clearly meant to represent an infected.

It’s human nature to soften our understanding of what frightens us. Yes, the mask is still unsettling, but there’s something oddly affectionate in the way the community incorporates this image into ritual.

The island’s ceremonial use of infected imagery — like the red-eyed mask — suggests that the infected have become mythologized. This isn’t just fear; it’s folklore. As with most insular societies, superstition fills the void left by broken science. The infected become gods and monsters, cautionary tales told to children in a world where bedtime prayers no longer apply.

We’ve waited Almost 20 years for closure.. just to have the third installment broken into another three movies

Honestly, I was pretty ticked off that the 28 Years Later expansion was being told over three separate movies — this one that released in June 2025; 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple (please don’t ruin a good thing); and another film that’s currently in development. I’ve mentioned several times: it has been almost 20 years since the last movie. Could we not have a concise ending to the series? In my opinion, every piece of good media — show, movie, book, whatever — is dependably always dragged out way too long and absolutely ruined. What’s worse than soiling an already dead plot point is ruining the integrity of the series itself; The Walking Dead franchise is a prime example of this.

However, considering there is a lot to be covered between the 28 Weeks and Years installments, it would be unfair to demonize the creators for their choice to spread these adaptations over several movies, so I should just accept that. This film gave us a look into how society has attempted to ‘regroup’ after catastrophe, as we follow characters from an isolated sanctuary. Outside of how the living have adapted, we also learn how the infected have adapted and evolved, groundwork that is important to know. There’s still much more to be explored in this new universe, and it’s fair to say that squeezing it all into one movie would’ve convoluted major plot points, restricted character development, and had an overall bad impact on the series.

I will say that one of the funniest parts was at the very end where Spike decides to go out to the mainland on his own and “walk until he cannot see the sea anymore,” and there’s a group of rando folks in colorful tracksuits doing parkor off a short cliff and anniliating these infected in ways that are only to entertain themselves. Of course, it should be mentioned that the first of this group to make contact with Spike has an upside-down religious cross hanging from his neck and fanes being super chill. Of course, we can presume that this person is the same child we saw run into the church at the very beginning of the movie (I’m sensing some Station 11 vibes).

In the end, I can appreciate that there’s a lot to explore 28 years after the original outbreak. The final moments — when the Jimmy Gang hangs an infected upside-down — call back to Spike’s first day on the mainland, where he witnessed the same imagery. Beyond introducing other sanctuaries across Europe, the film hints at broader questions: how have the infected changed? What kind of people survive on the mainland — and how do they manage the infected? Does the Jimmy Gang’s upside-down cross signal religious rejection or something more symbolic? Even amidst all the brutality, the story reminds us that empathy and humanism still persist, however rarely — and that might be the most important takeaway of all.

What did you think of the movie? Did it service the franchise well? Anything you want to mention that I haven’t or want to build onto? Feel free to share your thoughts below!

Leave a comment