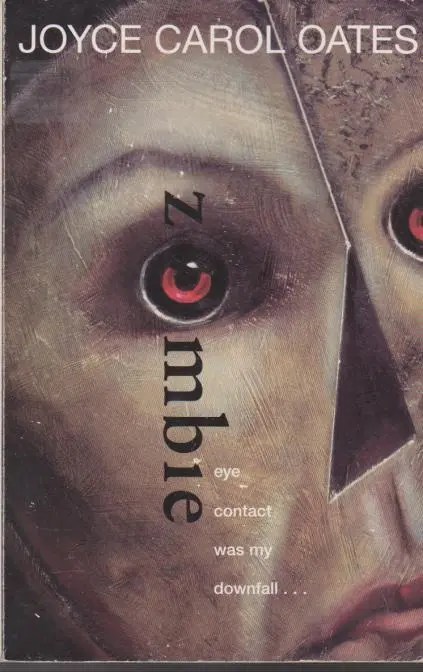

Joyce Carol Oates’ Zombie is one of the most psychologically disturbing horror texts of the late 20th century, and not in a way that feels gothic, mythic, or metaphorical. This is horror stripped of artifice. No ghosts, no jumpscares, no cozy resolution. Instead, Oates offers a claustrophobic, nausea-inducing narrative voice — the interior monologue of Q. P.

Reading Ahead

Zombie is presented as the personal journal of Quentin P. (or Q. P.), a convicted sex offender and mentally ill man in his early thirties who has recently been released from a psychiatric facility. Quentin lives with his emotionally repressed parents in a Midwestern town, working a menial job, occasionally seeing a court-appointed therapist, and keeping up appearances just enough to stay off the radar.

But beneath the surface, Quentin is consumed by a fantasy: to create a “zombie” lover — someone who is silent, obedient, and devoted only to him. He doesn’t want a partner in the romantic sense; he wants ownership over another human being’s body and will. The idea is that if he can destroy part of the brain that controls free thought and resistance, he’ll be able to make the perfect companion.

Quentin begins stalking and selecting young men — typically Black, Asian, or Latino, and often unhoused or estranged from their families. He invites them to his home under the pretense of sex, drugs, or shelter. His MO involves drugging them, sometimes attempting crude surgery, and either killing them outright, assaulting them, or discarding them when things go wrong.

The journal entries document his failed “experiments” in increasingly disturbing detail. One of the most horrifying scenes is when Quentin uses a household hand drill and an ice pick to perform a makeshift lobotomy on a young man he calls his “Zombie.” He believes that if he hits the right part of the brain, the man will survive in a docile, obedient state. The procedure fails, grotesquely. The victim either dies or becomes unresponsive, and Quentin must get rid of the body.

What makes this even more disturbing is Quentin’s tone. He writes in broken sentences, fragments, and sometimes childish drawings, with no grasp of the horror of his actions. To him, he is the victim: of parents who don’t understand him, a system that surveils him, and boys who “betray” him by trying to run or scream.

The book never ends with Quentin being caught. Instead, he continues undeterred, refining his methods and growing more confident in his “mission.” The book closes not with justice, but with Quentin fantasizing about perfecting his zombie-making technique and finally finding peace through absolute control over another body.

There’s no redemption, no moment of reckoning. The horror lies in the unrelenting interiority of Quentin’s voice and how normalized his monstrosity becomes through the act of writing. He is allowed to explain himself, uninterrupted, in a way that implicates the reader in his delusion.

Q.P. as a Conduit for Oppression

Q. P. isn’t just a serial predator; he’s a failed experiment of repression and privilege. The horror here is not supernatural, it’s systemic. He comes from a white, upper-middle-class family that actively suppresses language around queerness, violence, and illness. His sexuality is barely mentioned outright, except in panicked, euphemized fragments, but the story is saturated with it: voyeurism, internalized shame, desire warped by guilt until possession becomes the only outlet. His family infantilizes him, blames his victims, and insists that Quentin is a “good person.” All while evidence mounts that he is hunting vulnerable young men of color, mostly from working-class or unhoused backgrounds.

That dynamic is no accident. Quentin’s sense of entitlement — to bodies, to silence, to consequence-free indulgence — is framed not as deviant, but as inevitable. The class and race imbalance is never named by Q. P. himself (he doesn’t have the language or the empathy for that), but Oates writes it in anyway. She shows how monsters are not born in dark corners, but shaped in daylight by neglectful institutions and the families that protect them.

Quentin doesn’t want a relationship. He wants ownership. He wants to empty someone out and fill them with himself. The image of the “zombie” becomes a perverse dream of love without agency: a lobotomized partner who never talks back, never rejects him, never leaves. This is horror as perverse intimacy, not just murder.

There’s no moral to this story. No justice. No escape hatch. Oates doesn’t give us a detective to follow, or a survivor to root for. She denies us that distance, and that’s what makes Zombie so terrifying.

Girl, the Writing…

Oates writes this novella in first person, using an erratic, broken style — full of caps, sentence fragments, misspellings, obsessive underlining. From what I’ve read, some readers quite liked this and thought it supplemented the story in making Quentin seem more erratic and uneasy. Honestly, this element made me roll my eyes quite a bit. I think [mis]using grammar and syntax to evoke the ~deeply disturbed and and wild mind~ of Q. P. is kind of lazy. And, a bit cringe. Maybe that’s just how it rubbed me, but when I see a page pull of lines, ampersands, and misspelt words, I’m not thinking, “wow, this person is so disturbed that they cannot even coherently form a thought or finish a sentence!’” It feels like Oates didn’t actually know how to conceptualize Q. P.’s character and cheaped out.

Of course, JCO is a prolific writer and who am I to call her writing lazy? Her name on the cover of this novella is what initially piqued my interest.

Feminist Horror and the Anti-Spectacle

Reading this through a more critical lens, we can situate Zombie within horror traditions — specifically, its departure from the supernatural in favor of psychological horror and true crime realism. By refusing to make Quentin a charming antihero or give readers a safe narrative arc (like a detective or survivor), Oates strips horror to its most uncomfortable and morally ambiguous core. This idea is widely discussed in horror studies and feminist horror theory. The horror is not only what Quentin does, but that no one stops him. This discomfort is what makes this novella so deeply unsettling.

This approach aligns with trends in feminist horror theory, particularly what scholars like Carol J. Clover and Barbara Creed have explored: that horror often acts as a mirror to societal fears, especially around gender, sexuality, and power. Where traditional horror might present a monster as an external threat to be vanquished, Oates embeds monstrosity within the mundane. Quentin is not a vampire or a demon, but merely a product of white male privilege, wealth, and unchecked desire. In feminist horror analysis, this positions the monster not as “Other” but as frighteningly familiar, woven into the fabric of everyday life.

Oates’ refusal to sensationalize or romanticize her subject also echoes what some critics call the anti-spectacle in horror: the denial of audience gratification. We’re not allowed to root for a hero, cheer at a takedown, or feel relief. The language is flat, repetitive, devoid of flourish — mimicking Quentin’s dissociation and forcing us to dwell in it. This technique draws on what horror theorists describe as abjection (a term from Julia Kristeva), where the horror comes not from external monsters but from a collapsing of boundaries — between body and self, good and evil, victim and perpetrator.

By centering the narrative voice of a sadistic predator, Oates withholds the ethical clarity that most horror stories, even the bleakest ones, tend to offer. She doesn’t condemn Quentin outright — she lets us listen to him, uninterrupted, and dares us to sit in that unease. That’s the true horror: being made complicit, being denied distance. And in doing so, Oates challenges the genre itself — asking not only what we find frightening, but why we keep coming back to it.

All in all, Zombie is not fun. But it’s unforgettable. A brutal, clinical examination of repressed desire and the violence it can birth when left to rot. Essential reading for anyone interested in horror that cuts straight to the nerve (but I will not be reading this one again).

Leave a comment